-

Look Magazine - Birds In Far Pavilions

-

Look Magazine: Birds In Far Pavilions, Nusra Latif Qureshi

-

Nusra Latif Qureshi’s exquisitely painted vignettes consider histories obscured, lost and frayed, writes Matt Cox, Senior Curator and Artist Liaison, Tilt Industrial Design.

Nusra Latif Qureshi: Birds in Far Pavilions is the first major solo exhibition of the Melbourne-based artist, whose intruiging and allegorical paintings speak to the persistence and resonance of a painting across time and place, as as creative process, a medium of exchange and as an object of contemplation and fascination. Drawing on both historical and contemporary referencess, Qureshi works in the space between tradition and experiementation, in a practice that extends to collage, photography and installation.

Born in Pakistan, she trained at the National College of Arts in Lahore, where she learnt the painting traditions that had been brought to the Mughal courts from Persia in the 16th century and developed in the region.

This exhibition traces Qureshi’s 30-year career, from her early paintings in Lahore in which she began to reimagine traditional forms, to their zenith beyond the page with a newly commissioned installation. It includes the subtle, yet powerful suite of paintings for which Qureshi received the Bulgari Art Award in 2019, which speak to her experience of moving to Australia in 2001, and offer a window into the rich and complex history of Pakistan while bearing witness to the conflicts and consequences of colonialisation.

Qureshi remembers growing up in the city of Lahore and her family outings to visit the 17th-century Mughal tombs and gardens that not only survived the decline of the Mughal empire, British occupation and the partition, but continue to enchant and inspire. And although Lahore remains a more site of Mughal culture and education in Pakistan, Qureshi reminds us that it is also a site of great loss followng the collapse of the Mughal Empire and the annexation of the Lahore by the British East India Company. Qureshi laments that many of the paintings, swords, textiles and pulkhari (embroidered shawls) were hidden, damaged or removed to collections overseas. It is this sense of history; broken, fragmented, wonderous and beautiful, triumphant and traumatic, remembered and forgotten, but always present, that continues to captivate Qureshi’s attention and interest.

Equally present in her childhood memories are the eucalyptus trees that shaded her family garden and threatened to fall during wild storms. Introduced by Australian hydro-engineers, the trees became a vernacular part of the city’s landscape and prophesied Qureshi’s later interest in the transfer of people, culture, fauna and flora, which was such an informative part of the the British colonial enterprise.

-

-

When she arrived in Melbourne in 2001 to study at the Victorian College of Arts (VCA) it was after completing her training at the National College of Arts (NCA), Lahore, with its own development entrenched in colonial history. With the British annexation of the Punjab in the 1840s, the courtly workshops all but collapsed. Artists instead found work painting people and scenes for British patrons. It was also the British, somewhat paradoxically, who set to restoring the painting traditions of the Mughal courts through art and craft schools like the Mayo School established in 1875 and first directed by JL Kipling (father of the author Rudyard Kipling).

In 1947, following the dissolution of the British rule, the region was partitioned and the states of Pakistan and India were created, leading to widespread migration and violence. Despite this rupture – or perhaps because of it – the National College of the Arts led a revival of Musaviri (miniture) painting in the 1980s. Qureshi was among the first generation of women graduates who not only altered the content and subjects of their paintings to reflect personal interests but to also gain international attention.

Historically, musaviri painting was conceived to illustrate mythical tales or epic poems within relatively formulaic and coded traditions. So, one might ask, how does a contemporary painter like Qureshi, working in an environment where there is an emphasis on authenticity, originality and creativity, contend with the characterisation of her paintings as ‘traditional’? Qureshi might respond by saying that her painting should be freed from concepts of the traditional that fixate culture within a distant past. Instead Qureshi sees tradition as offering potential for reinvention through a revision of techniques, transfiguration and recontextualisation, in what she describes as a living and potent evolving language.

Using coded iconography, appropriation, cutting, collage, fine lines, torn edges and imagery, both violent and seductive, Qureshi creates layers of tension hidden beneath beguiling surfaces. Through the introduction of colour schemes, motifs and other elements from historical sources and earlier works, Qureshi teases out associations and fragmentary, sometimes contradictory, narrative components, without surrendering her story in its entirety. Hers are not the history paintings conceived retrospectively with a finite grasp on events, but subjective interpretations open to what might have been, or what could be. For Qureshi, narrative does not need to unfold in a linear fashion. Her paintings present multiple intersecting moments simultaneously, that, as other authors have suggested, brings her past in another place and her present together within a single image.

Qureshi’s training required copying paintings from black and white illustrations found in library publications with little deviation or experimentation. It was a process-based training that priveleged over creativity.

In the production of wasli paper, for example, students burnished layers of handcrafted paper with agate or shell. They stained their own paper and made brushes from squirrel fur. Yet, with little opportunity to view paintings in manuscripts, she trained without access to original artworks, a situation that fortuitously helped her translate the language of musaviri paintings into new forms. It also functioned to excite Qureshi’s interest in collage and appropriation as tools for reevaluating and recontextualising archival images.

Qureshi’s process is considered and acutely methodological, exemplifying a precision and dedication to materials that one might expect from her training, but she is equally careful to allow space for chance association and emotion. She thoughtfully selects paper and mixes pigments and waer in mussel shells until they turn into a satisfactory and workable medium. Her chosen colour palette expresses a spectrum of highly charged intellectual and emotive responses, specific to each body of work. From her desk, she can reach templates on tracing paper that assist her in reproducing recurring motifs such as birds and hands. Her paintings are produced over prolonged periods and are often left to sit idle in a drawer for a week or a month, while she ponders their possibilities. Her process – in which she commences, stalls, considers and returns – is reflective of her desire to deconstruct and reimagine history. The techniques of abstraction, fragmentation, collage and mirroring are some of her favourite devices for doing this.

-

-

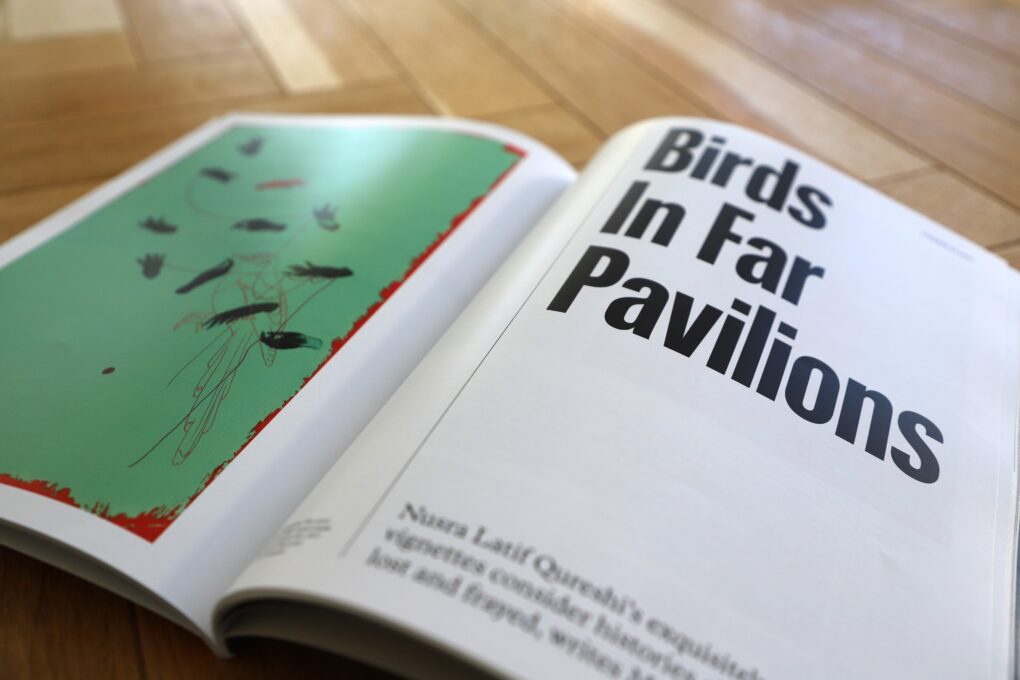

Images that appear to be mirrored or folded on themselves are in fact incomplete and assymetrical, reflecting uncertainty and inequality, while losses are remembered on Qureshi’s pages as an absence, a darkened impression, a void, a negative space. In other paintings she considers the violence of colonial history while drawing on weaponry, both historical and modern, as objects of macabre fascination. Spheres, circles and ovoids are recurring motifs and symbolise the globe, the womb, fecundity and rebirth. Hands, birds and solitary female figures occupy many of Quresh’s paintings and offer narrative and allegory.

Birds have a special place in Qureshi’s oeuvre. For Qureshi, the motif of the bird is a recurring and versatile one; birds carry with them the idea of flight and migration, even freedom, but Qureshi’s painted birds are seldom innocent creatures. For her, birds carry traits of human nature – mostly negative ones, habit, mystery, intrigue and cunning, and as such they offer a proxy for expressing emotions and ideas not possible or acceptable through the painted human form. Like people, they are observers, victims and agents of history.

Speaking with Qureshi, she fondly remembers her days at the VCA under the tutelage of Allan Mitelman, whose forms resonated with her own practice. Jon Cattapan and Charles Green offered a supportive environment, and Virginia Fraser (fellow student, writer, curator and collaborator of the artist Destiny Deacon) became a good friend and translator of Australian culture. Together, they discussed issues regarding the history of colonial relations in Asia and Australia. Folloiwng these exchanges, Qureshi began a new phase of her work including installations that deal with the layered and parallel histories of British colonialism in Asia and Australia. Where her paintings present an arrangement of sometimes divergent subjects and objects brought into association within a scene, her installations recombine the various components of the paintings in three-dimensional space.

For the exhibition, Qureshi has created a new installation, Museum of Lost Memories, borrowing objects from the Art Gallery’s collection to stage a unique, site-specific and theatrical enquiry into the collection practices that reflect the global entanglements of colonialisation. Selected objects, paintings and photographs from the Art Gallery’s collection are arranged in historical showcases (borrowed from the Powerhouse Museum). These artworks sit among objects from her own studio; items found, purchased and collected. By bringing those items together she makes visible the modes of private and public collecting, revealing layers of contradiction, conflict and dialogue across time and cultures, and in this act of reimagining, Qureshi invite the viewer to join her in untangling our relationship to history and to each other.

Matt Cox, Senior Curator and Artist Liaison at Tilt, was previously Art Gallery NSW Curator, Asian Art

-

Matt Cox, Senior Curator and Artist Liaison, Tilt Industrial Design -

Latest news and insights

-

Enquiries

New business — studio@tilt-industrialdesign.com

Careers — studio@tilt-industrialdesign.com

Press & media — marketing@tilt-industrialdesign.com

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to land, waters and community. We celebrate the value and diversity of First Nations art forms, cultures and languages, and their ongoing significance today. We pay respect to Elders past and present.